Left Neo-Orientalism is a (Problematic) Thing

A note on the Empire Podcast as a symptom of moral flexibility lurking on the left

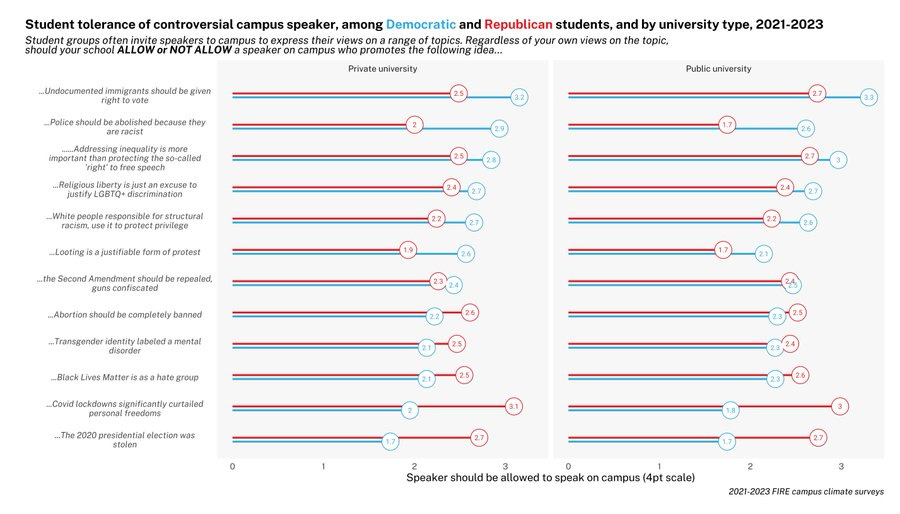

One thing that’s become abundantly clear since October 7th is that the global left, including academics and activists, is not so awesome at consistently applying its avowed moral principles. To be clear, and as my coauthors and I show in our forthcoming article in the American Journal of Sociology, “moral flexibility” is a problem on both the right and the left. Of course, each side denies that it shifts its moral standards to suit its interests, but check out our evidence and see if you’re convinced. And here’s another suggestive piece of evidence (h/t Thomas Wood):

But if both the right and the left (and all of us) tend to apply stringent moral standards to the ‘other side’ while making excuses for our own side, it’s not always so clearwhat the relevant sides and standards are. That is, moral flexibility may be at work where we don’t expect it— i.e., even when political partisanship isn’t so explicit and when the people expressing views present themselves as motivated not by partisanship but by truth.

So in this short post, I’m going to try to clarify one aspect of the leftist moral flexibility we’ve seen on display since 10/7, by giving it a name and definition and by providing very concrete evidence of this tendency among avowed truth-seekers who exhibit more partisan moral flexibility than they would care to acknowledge.

Here’s my proposed name for this tendency:

Left neo-orientalism

And here’s my proposed definition:

A tendency to hold (non-White) actors from the Global South to lower moral standards than (White) actors from the Global North

Obviously, I’m being ironic and provocative in proposing this name. Since Edward Said’s classic book, “orientalism” has become recognized on the left as a great moral sin, one that’s emblematic of Western imperialism, at least in the middle east. Let’s just say that not too many leftists want to think of themselves as orientalists. But I’m suggesting that a new form of orientalism has emerged on the left, whereby in their zeal to vilify empire, they’ve come to exoticize the formerly colonized as morally inferior. Yes, this is a version of the “soft bigotry of low expectations.”

Left Neo-Orientalism on the Empire Podcast

Evidence for left neo-orientalism is abundant on the wildly successful podcast Empire (20 million downloads as of December 2023), which is co-hosted by the historian William Dalrymple and the journalist/historian Anita Anand.

I’m not picking on Empire because it’s the worst offender. Nor do I think the podcast is irredeemably offensive. To the contrary, Dalrymple and Anand are serious, committed scholars. And I appreciate this podcast to a significant degree and have learned a great deal from it. But I’ve also come to see it as suffused with left neo-orientalism, which mars and distorts their treatment of various historical and contemporary cases.

There are various examples of this throughout the series, but I’ll zero in on one especially clear and vivid case. It emerges from a compare & contrast across two episodes:

Episode 40 (March 27, 2023), an interview with Israeli historian Tom Segev entitled Origins of the Israel-Palestine Conflict

Episode 123 (February 14, 2024), an interview with Lebanese historian Kim Ghattas, entitled Hezbollah: The Party of God

Each episode is pretty much as advertised, though the first episode is narrower than what you might infer from its title. In particular, it’s narrowly focused on the British conquest of Palestine, especially the 1917 Balfour Declaration and its consequences. Unsurprisingly, Dalrymple and Anand are not fans of the Balfour Declaration, viewing it as an illegitimate promise of Palestinian land to the Zionists. They’re quite sure that if it weren’t for Balfour, the political history of the last century ‘between the river and the sea’ would have been much better, certainly for Palestinians.

For his part, Segev repeatedly labels the Balfour Declaration “irrational.” What Segev means is that the Balfour Declaration served no discernible strategic interest for the British and that it was rooted in Lloyd George and Balfour’s ambivalent attitudes towards Jews (attitudes that were generally representative of British elites). On the one hand, they felt a certain amount of contempt for Jews/Judaism coupled with fear of Jews’ purported transnational power, at least in the context of perceived Jewish capacity to influence wartime alliances. But on the other hand, Lloyd George and Balfour were Christians who saw the restoration of Jewish sovereignty in the Holy Land as potentially a good thing.

For their part, Dalrymple and Anand seem to agree with Segev’s assessment, as they do not challenge it in any way. Rather, they seek only to add a complementary critique that they sound in many episodes (see especially two episodes prior, on the Sykes-Picot Agreement): that Balfour ran roughshod over the indigenous people’s interests and wishes.

Here’s the key exchange with which the episode concludes (from minute 48:00):

Segev: (The) Balfour (Declaration) is what happens when you take decisions under such a strong impact of your beliefs & your hopes & your fantasies…

Dalrymple: With little knowledge of the territory & no interest in the people who are living there

Segev: Exactly… the dangers of irrational decision-making. That’s… what I think the Balfour Declaration teaches us."

OK, so if you’ve read my previous posts (A & B) on the intractability of the Israel-Palestine conflict, you know that I think Dalrymple (and Anand elsewhere) is being too simplistic in his construal of “interest in the people” and “knowledge of the territory.”

But that’s not what I want to focus on here. I want to zero in on the charge of “irrationality” that Segev levels at Balfour, to which Dalrymple and Anand offer no objection.

Here’s what I wrote in my notes when I first listened to this episode:

Where do they get off being so prejudiced towards [the British elite’s] religious motivations? We’d be respectful of them if they weren’t Christian or Jewish, wouldn’t we?

It turns out this was a prescient comment on my part.

What do I mean?

Well, let’s now jump to the episode about Hezbollah. In particular, let’s listen to their discussion about suicide bombings, which Hezbollah first introduced into the region, with a November 1982 bombing of IDF headquarters in the southern Lebanese city of Tyre, one that killed 75 IDF offices as well as at least a dozen Arab prisoners. The most notorious Hezbollah suicide bombings were of course the April 1983 bombing of the Beirut U.S. Embassy (“killing 32 Lebanese, 17 Americans, and 14 [others]”) and the October 1983 bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut, which killed 243 U.S. service personnel (Hezbollah denied responsibility).

Let’s be clear: Neither Ghattas nor the co-hosts evince any support for suicide bombing. Indeed, Anand explicitly calls them “grotesque.” But overall, the discussion of Hezbollah in general and suicide bombings in particular refrains from passing judgment. Consider this exchange (at 38:54)

Ghattas: I think it’s very important to understand — and I want to make clear that I’m explaining rather than justifying.

Anand: Understood.

Ghattas: They’re not just sending boys to die. They have a cause…

Anand. Hmm.. (approving)

Ghattas: … which is Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon. And they have a lot of support… From 1982 to 2000, Hezbollah grows into a resistance movement against Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon… and does actually have a fair amount of respect— Hezbollah (does)— amongst other parts of Lebanese society and they end up successful, in a way. Because the Israelis, after a decades (long) war of attrition end up withdrawing in the year 2000 from south Lebanon, and it is the first time that armed struggle by Arab groups, army, etc. liberates Arab territory. Everything else has been done by peace accords. So they set an example. The problem is, as you say Anita, they’ve also become entrenched in Lebanese politics, they’ve become corrupt, and they further corrupt Lebanese politics, and then they turned their guns against the Lebanese.

So in “understanding” Hezbollah, Ghattas thinks it’s important we recognize that Hezbollah was quite “successful” in the eyes of many Lebanese, setting a positive example for Arabs to emulate more generally: land can be liberated through armed struggle— cool!

(Nowhere in the discussion is there recognition of the fact that Israel’s invasion of occupation of Lebanon was qualitatively different from other Israeli wars and occupations; most notably, Israel never made any move to initiate Jewish settlement. That’s because Jewish recognition of Lebanon as distinct from the Land of Israel goes back to biblical times. And so insofar as Hamas or others are prone to infer from Hezbollah’s success that it’s possible to drive Israel out of “Arab lands” via military force, they’re making a big mistake, reflecting the more general failure to reckon with Jewish national narrative, a matter I discussed in Part A and will return to in Part C).

Let’s dig down into this “understanding” of Hezbollah by going back a few minutes earlier in the episode and listening to the Empire crew discuss the origins of suicide bombing (from 34:13)

Anand: Tell us about the origin of suicide bombing being the weapon of choice of Hezbollah.

…

Dalrymple: Where does he get the idea from?

…

Ghattas: A genius, Machiavellian mind that came up with this idea….

Anand: Grotesque…

Ghattas: Grotesque, ya. Which was dismissed at the time because everyone thought, who on earth, is going to be willing to be blown up himself……

… every time people think, OK, it’s just a one-off. You know, all the way back to the U.S. hostage crisis in Tehran: “It’s just a one off.” The kidnapping of the first American in 1982: “Oh, interesting. It’s just a one-off.” The bombing of the Israeli headquarters in Tyre: “Oh, well that’s strange, that’s new” Bombing of the U.S. embassy: People start slowly to realize that there’s a whole new direction that this civil war in Lebanon is being taken into by new actors on the ground. And then you have the Marine bombing in October, 1983.

Dalrymple: So Kim, at the same sort of time, in the Iran-Iraq war, you’re beginning to have those horrific reports of young men being given the keys of heaven…

Anand: No men: boys. Boys, children!

Dalrymple: Boys! Ya, boys. Holding little keys, walking through minefields, to clear them for the Iranian tanks. Now does that precede the suicide bombings that you’re getting in Lebanon or is it part of the same thing at the same time?

Ghattas: I wouldn’t know chronologically whether it precedes or whether it’s parallel. But it’s part of the same revolutionary fervor and desire for martyrdom...

Dalrymple: Martyrdom?

Ghattas: For a greater good and a different world vision that, you know, may not make sense to you or me but makes sense to them. You know, I don’t think we should dismiss this as totally irrational. It’s just not what is familiar to me. But it is very effective for what Iran is trying to achieve— or the Islamic Republic of Iran. And in Lebanon, you also have a long history of car bombs before you had suicide bombers (emphasis added)

Anand: Hmm… (approving)

Dalrymple: Which had been there right back into the twenties and thirties in Palestine that the early resistance fighters, the early Zionists, were letting off car bombs in the Jerusalem marketplace.

Ghattas: Absolutely yeah, The Haganah and others, yeah

Did you notice the whataboutism at the end, there? That’s a signal that we’re in the land of moral flexibility. And it’s interesting that it plays out as a kind of improv, based on the ‘yes, and’ principle. First Ghattas implies that suicide bombings aren’t so new because they draw on the history of car bombings, and then Dalrymple chimes in that the latter were introduced into the region by Zionists. The upshot is that the listener is invited to ponder whether maybe suicide bombings are just a slight variation on something that’s ultimately the Zionists’ fault. Never mind that Ghattas had just finished explaining how it took years for Israel, the U.S., and others to accept that suicide bombing was really happening since it was so incomprehensible that people would willingly do this (or send their comrades— let alone kids— to do it). By contrast, if you look back to news reports of the first car bombing “fully conceptualized as a weapon of urban warfare” (by the Lehi, in 1947; not earlier by anyone, and not by the Haganah), it is not regarded as something particularly novel. So, they seem to be working overtime to downplay the moral break that suicide bombing represented.

To be sure, whataboutism is a somewhat speculative basis for alleging moral flexibility of the form I’ve defined as left neo-orientalism. The more concrete evidence emerges from the compare-&-contrast with the Segev interview. Recall how they had all agreed with Segev’s characterization of the Balfour Declaration as “irrational?” Contrast that with how they agree to what is essentially the opposite move: Ghattas’s rejection of suicide bombings (including the conscription of children into suicide wave attacks) as “irrational.”

Why? Well, it’s “effective” given Iran (and Hezbollah’s) goals! And then there’s that “revolutionary fervor” we apparently should respect— even when we’re talking about indoctrinated children.

One wonders: What precisely would it take for them to allege that indigenous middle easterners (“orientals”) were behaving irrationally &/or that their religion was leading them to misconstrue their true interests? Even as Ghattas acknowledges that Hezbollah has been quite problematic for Lebanon, she can’t bring herself to level such criticism. Nor does Dalrymple or Anand’s “grotesque” or “horrific” lead them to challenge Ghattas’s pious pronouncement about the need to refrain from passing judgment. We’re only here to understand, not to judge, don’t you know! Ah, but if the protagonist is perceived as White and/or a Westerner? That’s a different story: How can we not pass judgment then?

Conclusion

So left neo-orientalism works like this:

When the protagonist is Britain (or a Western agent more generally, including Israel/Zionists), we must be quick to assert what’s in their interests and to dismiss religious or cultural motives as “irrational.” Things always go badly when your decision-making is distorted by irrational motives, don’t you know?

On the other hand, it’s not OK to ever call global southerners irrational! When it comes to them, it’s not our place to judge. Rather, we must bend over backward to understand why it makes sense that they’d adopt any means that effectively realizes their interests. And who are we to quarrel with their goals?— it’s certainly no problem if they are religiously or nationally motivated. Why is it no problem? Because we’re applying lower moral standards for them.

This post is only meant to scratch the surface of the phenomenon of left neo-orientalism. A lot more can and should be said about it, on Empire and beyond. For now though, I think it’s important to be able to recognize it and to root it out. True we all do this! But two wrongs don’t make a right. And just as facts must be the foundation for truth rather than having “truth” shape our selection and interpretation of facts, justice must be blind to the protagonist we are judging. And we must certainly pursue justice, and beyond it, to virtue. How else are we going to decide what to do?