To Lump or Split? Lessons from Penslar vs. Wolfe's Use of "Settler Colonialism" to Analyze Zionism

Part B on the Intractability of the Israel-Palestine Conflict

Note: Rather than do a single part b to my essay on the intractability of the Israel-Palestine conflict, I’m going to do 3 or 4 posts (i.e., there will be part c, part d, and perhaps part e). Here is part b. I’ll also try to do these a bit more regularly.

We do it at cocktail parties. We do it in boardrooms. At research seminars. On the schoolyard. And of course on Twitter. In these and so many other venues, we spend a great deal of our time debating whether an event or object of interest is a member of category X (which means we’re equating it with items x1, x2, x3…) or category Y (items y1, y2, y3…). Oh boy do we fight about definitions and analogies!! A lot seems at stake in whether we decide to lump or split.

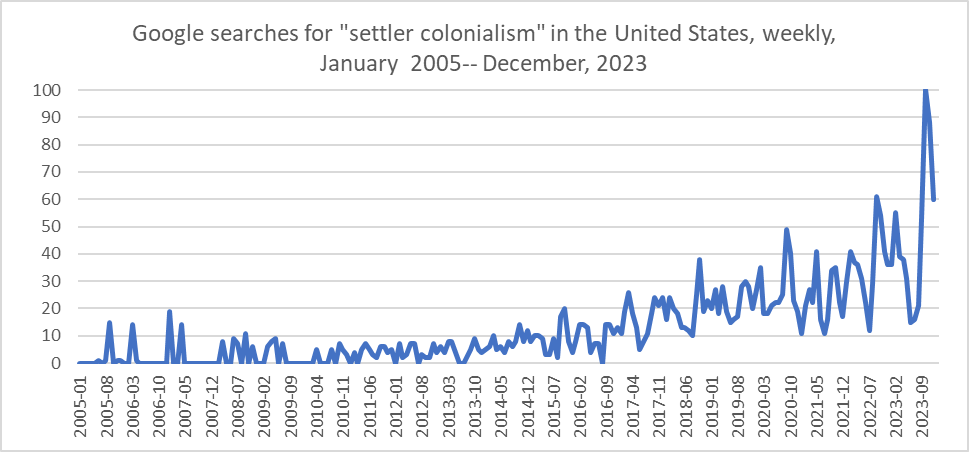

One prompt for such debates is when there is a new idea afoot in the land, a new proposal that is being widely shared for how to lump and split. Such a trend may be reflected in the rise of a new label, a label that is being deployed to group things that we used to distinguish from each other. This label may in turn be hotly contested by those of us stuck in our old ways of seeing the world, where the differences seemed more important than the similarities. Here’s a good example of such a trend:

Yep, “settler colonialism” is having its day. This term was used as early as the 1970s by such scholars as Rodinson and Said, but it was really supercharged by the late Australian historian Martin Wolfe. The objective of this label, according to Wolfe, is to lump together imperial-colonial enterprises that share the following feature:

“a sustained institutional tendency to supplant the indigenous population.”

Thus, for example, the United States (and the Americas generally) and Australia (and New Zealand) are good examples of settler-colonialism (with the “supplanting” in these cases brought about by the genocide, expropriation, and political disempowerment of indigenous peoples, on behalf of colonizing settlers whose settlements became the basis for sovereign political entities that enshrined the dominance of the empire’s language, culture, land-use regime, and economic organization). By contrast, such cases as India (under British rule) and Korea (Japanese) don’t seem like good examples of settler colonialism.

Other oft-cited examples of SC include South Africa and Algeria. But these are different from the first set, aren’t they? After all, Europeans/whites always remained a minority in both countries; moreover, settler dominance was substantially reversed in the former case and fully reversed in the latter. Furthermore, as we turn these cases over in our minds, and as we ponder the cases of SC noted above as well, the differences can begin to overwhelm the similarities (Hmm.. and should we even be considering the possibility of a non-European empire such as Japan engaging in SC? If not, why not? Such cases certainly seem plentiful; e.g. , e.g., and e.g.). When then is the SC label appropriate?

Of course, we haven’t even gotten to the case that really gets our lump-vs.-split juices flowing: Israel. If you’ve found your way to my Substack (and you’ve read part a), you know already that some folks (indeed, many academics, especially those “post-colonial” scholars who have embraced the term settler colonialism) think that SC is a useful term to describe the Zionist enterprise that led to the formation of the state of Israel (as well as its post-1948 governance model, and especially post-1967), whereas there are those who vehemently disagree, to the point of alleging that those who label Israel as a case of SC are driven by problematic (read: anti-Semitic) motives.

Thus for instance, when the Wall Street Journal’s editors criticized Harvard for appointing the historian Derek Penslar as co-chair of its Presidential Task Force on Combating Antisemitism, they included the following charge: “Mr. Penslar’s work on the history of Zionism isn’t uniformly extreme, but it shares an emphasis on ‘settler colonialism’ with the protesters who have harassed Jewish students on campus.”

The Journal seems to think that an “emphasis on SC” is problematic (reflecting biased activism rather than scholarship) whereas Penslar and many other scholars think SC can be useful. Who’s right?

Perhaps they are both right. Perhaps SC can be useful for certain purposes, but it is quite problematic if ‘emphasized’ to the point that it is the only framework that’s used, such that for certain purposes its use forces us to lump what should be split.

That’s basically what I argued in part a. I essentially argued if our purpose is to understand why the Israel-Palestine conflict is so intractable, we must recognize that the two sides tend to lump and split the Zionist movement very differently: For the Palestinian side, Zionism is a case of SC; whereas for the Israeli side, Zionism is a movement of national liberation. Moreover, we can’t resolve the debate by declaring that one side is right and the other wrong. The problem is that each side acts based on its theory of the case. And that means that if our goal is to explain the two sides’ orientation to the conflict, it will be a big mistake to pick just one side’s narrative. This very divergence in how the two sides lump vs. split helps to fuel the conflict.

In this essay, I’ll flesh out this analytic strategy by comparing and contrasting Penslar’s deployment of SC in his recent book Zionism: An Emotional State with how Wolfe deploys it in his (2012) essay “Purchase by Other Means: The Palestine Nakba and Zionism’s Conquest of Economics.”

Why do I think this comparison is instructive? Because Wolfe and Penslar each recognizes that it’s far from straightforward to classify Zionism/Israel. On the one hand, they largely agree as to the similarities between Z/I and other cases of SC. What’s more, they also exhibit some agreement with regard to how Z/I differs from the other cases. But they diverge in how they treat the differences(!!).

As we will see, SC is useful for Penslar because without this framework, it is hard to explain why one of the parties to the conflict— Palestinians and their supporters— react to Zionism and Israel as vociferously as they do. For Wolfe on the other hand, SC is useful because without it, it would be harder for him to condemn Zionism as a morally abominable enterprise. Whereas Penslar’s objective is explanation, Wolfe’s purpose is moral judgment. Moreover, and quite ironically, Penslar explains Wolfe. That is, Penslar sheds light on why Wolfe “emphasizes” SC (to quote the Journal) as much as he does.

Beyond this delicious irony and the caveat that we need to be alert to when scholars of politically charged topics are playing the role of scholar (Penslar) or of activist (Wolfe) and not lump them together all because they use the same analytic framework (as the Journal did), there is a more general takeaway from this exercise that’s simple to state upfront: There is never a right answer of whether to lump or to split. It always depends on our purpose. Which means that the most important question to ask is: Why are they— and we— lumping and splitting?

Wolfe: Israel is Settler Colonialism on Steroids!

In his article, Wolfe highlights two differences between Zionism and other enterprises he labels as SC. And over the course of his article, he adds at least four more differences. Here they are:

Zionist settlers weren’t drawn from a “unitary (imperial) metropole” (p.136) but from a variety of different countries (and few from Britain, the European imperial power in control of the land from 1918)

“The acquisition of Native territory (by Zionist institutions) was initially carried out in conformity with the existing legal system” (p.142) which “could not be swept aside or imposed the way settlers had dealt with indigenous legal systems in the USA or Australia (pp. 154-5).”

“Zionism presents an unparalleled example of deliberate, explicit planning. No campaign of territorial dispossession was ever waged more thoughtfully (p.137).”

Land was acquired on behalf of a people. “Conceptually, the idea of collective ownership on behalf of the Jewish nation diametrically reversed the US ideology of private property, which demonised Native ownership on the grounds of its collective nature (p.154).”

Zionist investments were “not conditional on the return of financial profit (p.140) and were not motivated to exploit local resources, whether natural (Palestine had no oil and is poorly endowed more generally) or human (Zionists emphasized “Jewish labor”)

The Zionist movement (and Israel) “rigorous(ly) refused… any suggestion of Native assimilation (p. 136).”

Ok, so what does Wolfe make of these six differences?

I’ll tell you in a moment but before answering this question, I encourage you to consider what you make of them. (I also encourage you to read his article first!)

My main reaction when I read the article was to be puzzled. One reason is that I wasn’t sure why Wolfe focuses on these six to the exclusion of all others. It seemed ad hoc. A second reason is that I’m not sure why he highlights the first two up front and then brings up the other four along the way. That seemed tendentious.

Why does this list seem ad hoc? Well, there are many other differences between Zionism and other cases of SC he could have focused on. For instance, an obvious and well-known difference is that Zionism fostered the resuscitation of an ancient language to become the basis for an everyday vernacular and modern literature. There is nothing like this in any other case of SC. Another interesting difference is that the Zionists were in some sense joining a pre-existing community of fellow co-ethnics/co-religionists. Another interesting difference: Not only did the settlers come from a variety of different countries beyond the metropole, they were a discriminated-against ethno-religious minority in these countries. Finally, in no other cases of European SC did the settlers include a substantial number of non-European immigrants who were indigenous to that land and/or the larger region. There are still other differences, of course. And if that’s the case, why is Wolfe only focused on these six differences?

A clue is that there is also no substantive reason for privileging differences 1 and 2 over the next four. The only possible reason for doing that, and for his selection of differences, is rhetorical. Wolfe is apparently not interested in considering all the ways that Zionism/Israel is distinctive, but rather in selecting those that help him make a particular argument. And he is organizing them in such a way these differences help him make that argument. That is, he has a tendentious agenda here.

In particular, Wolfe seems to want the reader to focus on differences 1 and 2 first because they are potentially troubling for his argument but can be handled relatively easily; by contrast, 3 and 4 are even easier to assimilate into his argument. For its part, difference 5 arguably causes the biggest problems for his argument; but he seems to think that by the time he gets there, he has enough momentum after tackling 1 and 2 and gathering steam with 3 and 4 that he is then in good position to assimilate difference 5 as well. And then since he seems to think difference 6 fits his argument and no other, he uses it as a clincher. Finally, there seems to be a straightforward reason he avoids the kinds of differences I noted above, beginning with the revival of Hebrew: They might lead the reader to consider the obvious alternative to Wolfe’s argument.

What then is Wolfe’s argument? And what is the argument he is avoiding and why? If read closely, the first paragraph of his conclusion provides the answers to these questions:

It may seem perverse to offer a narrative of Palestinian dispossession that dwells so obliquely on the Nakba. My intention has not been to understate the repeated enormities that the nascent Jewish state perpetrated in the Nakba. Rather, it has been to situate it in the context of the ongoing (in Saree Makdisi’s term, ‘slow-motion’) enormity that Zionists, with imperial and comprador connivance, had been conducting incrementally, day by day, for over half a century before the Nakba. In the absence of that context, the Nakba would make no sense. We might even agree with Benny Morris that ethnic cleansing was a spontaneous aberration that took place in the heat of warfare. In the preceding context of Zionism’s conquest of economics, however, the Nakba makes only too plain sense. There was no change of ends. The Nakba simply accelerated, very radically, the slow-motion means to those ends that had been the only means available to Zionists while they were still building their colonial state (p.159, emphasis added).

The bolded sentences point to an awkwardness for those who seek to ‘emphasize’ (to quote the Journal again) the “enormity” (i.e., enormous moral crime) of Zionism and Israel, as Wolfe does: Some of the best scholarship on the Palestinian dispossession in 1947-8 was conducted by Israeli historians— Benny Morris, in particular— who did not use a settler-colonialist framework. Nor indeed did contemporary Arab observers of 1948 such as Dr. Constantin Zureiq, who coined the term “Nakba” to refer to the embarrassing failure of Arab nation-states in their competition with the new Jewish nation-state.

This is the obvious alternative that goes unmentioned in Wolfe’s article: the conflict as one between two nationalist movements. After all, it is easy to find cases of “lightning dispossession” (Wolfe’s [p.134] description of what was distinctive about the Nakba) resulting from other conflicts between would-be nations in the context of imperial withdrawal. Think especially of cases where the zero-sum intensity of the conflict is such that it leads to ethnic cleansing, through some combination of mass killing, expulsion, and flight. The partition of Pakistan-India comes to mind; as does Smyrna in 1922. Tragically, there are many such cases. And they often have a religious element to the national conflict, as the Israel-Palestine conflict does.

Of course, every case of “zero-sum national conflict in the context of imperial withdrawal” (ZNCCIW) is different. It’s not clear whether we should lump or we should split, is it? But it’s also not clear at all why the Nakba isn’t more like one of these cases of ZNCCIW than it is a case of settler colonialism. Those differerences I noted can easily be read that way. As can any of the differences Wolfe highlighted, beginning with the first two. The use of legal means of land acquisition smacks of a people who, like other colonized peoples, had to work within the imperial system. And the fact that the Zionists weren’t co-ethnics with the withdrawing empire certainly reminds us of other cases of ZNCCIW.

Indeed, not only were Jews not co-ethnics with the withdrawing British, hey weren’t co-ethnics with any of the neighboring nation-states. As a result, they felt they had nowhere to flee to. Which is why— I would argue— Israel fought so fiercely and won. That is, Jews in Palestine felt they needed their nation-state to succeed in order to survive. Put differently, Zionism’s particular form of nationalism was essential to Israel’s victory in 1948. By contrast, Wolfe insists that the game was rigged from the beginning: the Zionists won because they had “preaccumulat(ed)” all the advantages of being settler colonialists.

But I digress. My objective here is not to explain why the Zionists won in 1947-48. What I’ve been trying to do is to reverse engineer Wolfe’s ad hoc, tendentious rhetorical strategy. And I’m arguing that differences 1 and 2 looms as a problem if your strategy is to emphasize SC and deny ZNCCIW.

So the problem for Wolfe is that one might think that these two differences threaten to undermine his classification of Zionism as a case of SC and point instead to the utility of classifying it as ZNCCIW. To counter this unstated alternative, Wolfe argues that these differences in fact point to an “intensification of, rather than a departure from, settler colonialism (p.136).” In particular, he argues that differences 1 and 2 “constitute linked elements in a uniquely developed programme of Indigenous dispossession (p.136).” In short, Wolfe brings in difference 3 (deliberate planning) to argue that Zionist institutions were supported and built by a transnational, Europe/U.S.-centered philanthropic support network designed to build up the foundations for an exclusively Jewish state and thereby dispossess the Indigenous people of the land. Since the network originated in Western countries and since it used the imperial system, it qualifies as SC. And the planned pursuit of national property and (institutions generally) reflects its goal of Palestinian dispossession.

With these first three differences taken care of, the rest falls into place. Collective land ownership makes sense given the need to create contiguous parcels exclusive to Jews and to keep land out of the hands of Palestinians. And the insensitivity to profit and the lack of interest in exploiting Palestinian labor simply reflect the desire to set up a colony that excludes Palestinians. Finally, the absence of a path for Palestinian assimilation into Jewish Israeliness is the clincher.

For Wolfe then, the logic of the Zionist enterprise laid the groundwork for the Nakba. If SC is defined by “a sustained institutional tendency to supplant the indigenous population,” then we have a clear case on our hands. Indeed, Wolfe argues that the differences between Zionism/Israel and the other cases actually make it the ur-case of SC! It’s the other cases that are weaker cases of SC. This is the paradigmatic case. It’s SC on steroids!!!

But there’s an obvious problem with all this, as we have seen: All of these differences can also be understood as reflecting the fact that Zionism was a Jewish nationalist enterprise. What’s more, the applicability of a nationalist framework becomes even more compelling when we consider a fuller list of differences between Zionism/Israel and other cases of SC, such as those I listed above. How else, for example, do you understand the resuscitation of Hebrew as a vernacular? Other cases of linguistic resuscitation that come to mind (think Gaelic or Ukrainian) are also part of nationalist efforts to recover from imperial domination. Why isn’t this one too?

More importantly, it should strike the reader as suspicious that Wolfe avoids even mentioning ZNCCIW as a possible framework for understanding the historical processes leading up to the Nakba. SC is presented as the only framework that can “make sense” of it. I think the answer is clear and is reflected in his concluding reassurance to the reader that he hasn’t been downplaying the Nakba and that indeed its “enormity” is even clearer when we appreciate its SC background. Here’s the problem to which Wolfe is trying to hack a solution: If we were to view the half-century leading up to 1947-8 as a zero-sum national conflict in the context of imperial withdrawal, it’s much harder to condemn Zionism and Israel as illegitimate. Rather, the the case starts to look more like a tragic outcome of the competition induced by the carving up the post-imperial world into nation-states than it does a particularly pernicious example of imperial criminality.

But guess what? There’s no reason why we have to choose one framework over another for all purposes. In particular, if our goal is explanation rather than moral judgment, we are free to apply these (and potentially other) frameworks in a bid to shed light rather than just generate heat.

Penslar: Why Do People Get So Worked Up about Zionism?

Enter Penslar. The key difference between Wolfe and Penslar is that Penslar is the more transparent, careful scholar. He isn’t up to any rhetorical mischief when stating his purpose for his exercises in lumping and splitting. His purpose is very clear and explicit: To document and explain the range of emotions elicited by the Zionist movement (in its various forms) and Israel from various parties over the last century and a half or so.

Penslar also explicitly considers both nationalist and settler-colonialist frames, devoting chapter 1 to the first and chapter 2 to the second. He is also clear as to why both frames are useful given the focus of the rest of the book: Depending on whose emotions you’re trying to explain, a different framework is necessary. Penslar argues that whereas one cannot understand Jewish emotional orientations to Zionism without a nationalist frame, one cannot understand the emotional orientation to Zionism by many of Israel’s critics without a SC frame. You will notice of course that this dovetails with my analysis in part a.

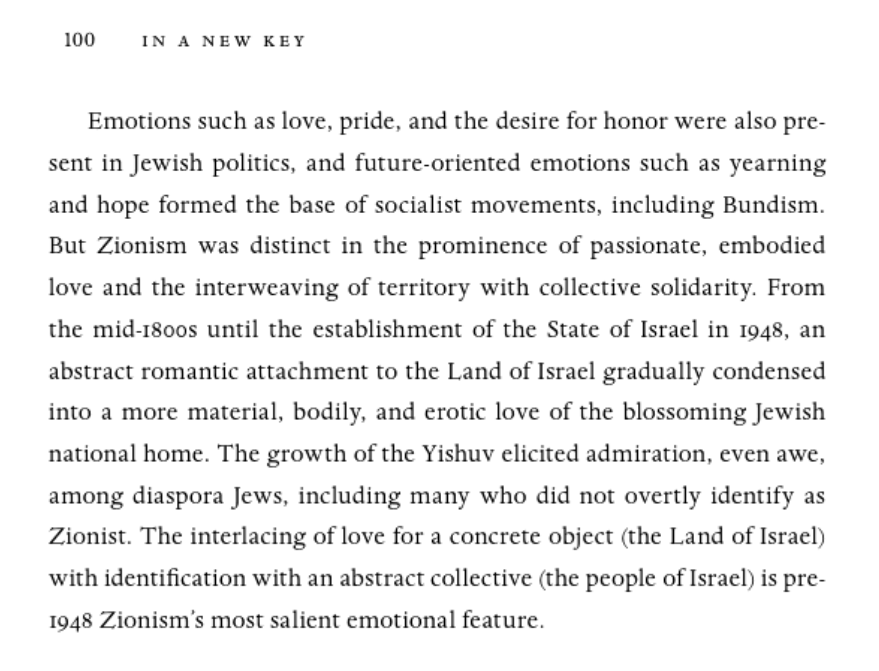

Here is Penslar’s summary of what was distinctive about Zionism in comparison to other early 20th-century Jewish social and political movements:

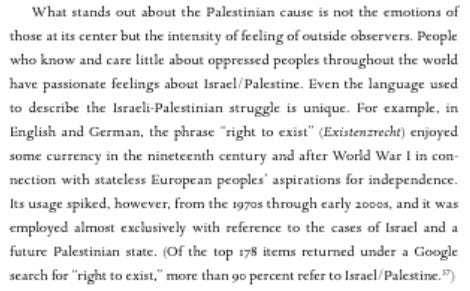

If Zionist Jews’ “erotic love for the national home” can only be explained with a nationalist frame, here is what Penslar argues can only be explained with a settler colonialist frame (p.219):

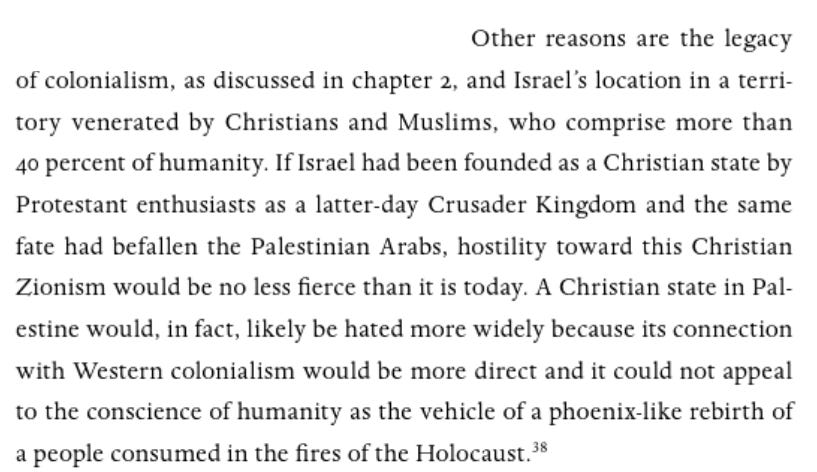

He goes on to say that some part of the distinctive “intensity of interest and passion” viz Zionism/Israel by “outside observers” is “manifold” and that Israel’s “Jewish character” is one of them. That is, some people just hate Jews. But he goes on to say that an important part of this distinctively intense antipathy can be traced to a more general antipathy for settler colonialism. He makes the point with an intriguing counterfactual:

It’s an interesting conjecture, isn’t it? And it’s not such an idle conjecture since to a significant degree, Christian Zionist activity in the mid-19th century laid the groundwork for (Jewish) political Zionism later in the century (see Penslar, pp. 25-29).

To be sure, it’s impossible to know whether Penslar’s conjecture is correct. It’s certainly plausible though. And it helps reinforce what was already a good reason to incorporate SC into an account of the history (and present) of Zionism and Israel: It’s otherwise hard to account for the negative response it elicits.

Indeed, it’s in this respect that I asserted above that Penslar helps explain Wolfe. Why does Wolfe consider only the SC frame and avoid any mention of the nationalist frame? Because it facilitates his denunciation of Israel as a moral “enormity.”

To be clear, Penslar does not think that SC is useful only in explaining hatred of Zionism by outsider critics (oddly, he has little to say about the importance of SC in explaining Palestinian antipathy towards Zionism; by contrast, this is central to Said’s classic treatment). Penslar also thinks SC is useful in explaining Zionists’ “attitudes and practices towards Palestine and Palestinians (p.76),” which (as Said argued) reflected a European-inflected chauvinism. In fleshing out that part of his argument, Penslar makes productive use of comparisons with particular cases of SC as they highlight important aspects of Zionism that might not otherwise be salient (from colonial New England: the struggle to subdue a foreign land; from South Africa: the concerns about demographic threat and consolidation of ethnic nationalism to counter it; from Algeria: legitimation of the settlers’ project by framing them as linked to ancient, exiled natives).

Unlike Wolfe though, Penslar doesn’t deploy SC once-and-for-all (indeed, the Journal is dead wrong to say that Penslar “emphasizes” SC), but as a device for sensitizing us to particular patterns that show up in Z/I and in some cases of SC but not in others. And more generally, Penslar emphasizes (!!) that it would be a major analytic error to lump Zionism with other cases of SC and be done with it.

Why indeed?

Quite simply, the reason is that however much SC is useful for explaining the antipathy of anti-Zionists and for illuminating some aspects of Zionist behavior, you simply cannot understand Zionism without a nationalist frame. As Penslar puts it:

Zionism was the only form of settlement colonialism that was also preceded and structured by an ideology. The motley Dutch, German, and Scottish settlers who comprised the Afrikaner republics did not arrive with a coherent national identity…. The first Afrikaans novel was published only in 1913; the Afrikaans Bible appeared twenty years later. In the Maghreb, the transformation of sundry Mediterranean communities into French Algerians was quick yet unchoreographed, and the pied-noirs’ dialect, pataouète… was not a literary medium in and of itself. Zionism, in contrast, was a coherent nationalist ideology, drawing on two competing and overlapping language-based nationalisms centered around Hebrew and Yiddish… The rudiments of the language were familiar to the vast majority of immigrants to Palestine. Along with knowledge of Hebrew came familiarity with the Jewish textual devotion to the Land of Israel; as Gurevitch and Aran put it, in Jewish culture, Eretz Yisrael (the land of Israel— EZS) was not merely ‘a place,’ but rather the ‘Place.’ Jews in Palestine, later Israel, mediated their perceptions of their surroundings through a textual screen.

In short, lumping Zionism with other cases of SC can be productive, but it crucially depends on your purpose. In particular, if you’re seriously trying to understand why Zionists and their supporters do what they do, you will be making a major error unless you also understand Zionism as (a distinctive form of) nationalism.

Coda 1: From Ideology to Toolkit

I’ll close off this essay with two points. First, I’d like to underline and reframe Penslar’s critical observation that “Zionism was the only form of settlement colonialism that was also preceded and structured by … a coherent nationalist ideology.” Penslar is correct of course, but I would put it less as a matter of “ideology” than— following Ann Swidler’s classic essay that essentially launched cultural sociology— in terms of a “cultural toolkit”— a repertoire of proto-Zionist ideas and practices that was shared by Jews from Lithuania to Salonika, from Bukhara to Yemen, and from Baghdad to Rome. Furthermore, to say that a proto-Zionist cultural toolkit “preceded” Zionism is to understate the matter. By the late 19th century, a Jewish cultural toolkit centered around the dream of a return to Zion went back more than 2500 years, with continual widening and deepening over the ensuing millennia.

Central to Swidler’s influential formulation is that we always “know more culture than we use” (ibid.) at any one time or situation, such that the full extent of this toolkit is revealed as times and situations change and we draw upon it to address those new situations. Thus the fact no Jews were political Zionists before the turn of the 20th century does not mean that Zionism was foreign to them. To the contrary, the default understanding in every (traditional) Jewish community was that Jews are in exile, and they are awaiting the arrival of the Messiah, to restore Jewish sovereignty over eretz yisrael (“land of Israel”). And so it should come as no surprise that Theodore Herzl was greeted as the Messiah in many communities. More generally, Jews throughout the world had at their fingertips proto-Zionist ideas and frameworks.

Consider the term Zionism. If you asked any pre-19th century Jew if he was familiar with the word “Zion,” they would likely have laughed at the absurdity of not knowing the word and pointed to the many places it shows up in the Jewish liturgy and song. Non-Jews sometimes do not appreciate how standardized Jewish liturgy is. Since the rabbinic revolution and with the partial exception of the practice in non-Orthodox movements since the 19th century, for at least a millennium and a half, Jews have prayed that “(their) eyes should witness (God’s) return to Zion” (implying Jewish sovereignty over Eretz Yisrael, centered in Jerusalem or Zion) three times a day. And every time Jews recited the ‘Grace after Meals,’ they thanked God for the “land that [God] parcel(ed) out as a heritage to our fathers, a land which is desirable, good, and spacious” and asked God to “have mercy on Israel your people, on Jerusalem your city, and on Zion the resting place for your glory.” In Asheknazi (northern European) tradition, these post-meal blessings were preceded by one of two proto-Zionist psalms that were familiar throughout the Jewish world:

“By the rivers of Babylon where we sat down and wept as we recalled Zion (Ps 137:1) ”

“When the Lord restores us to Zion— we will come to be seen as dreamers/prophets (Ps 126:1.”

Additional elements in the Jewish cultural toolkit included R Judah Halevi’s well-known ‘love of Zion’ poems from the 12th century. Consider how contemporary Halevi’s words would have sounded to a fin-de-siècle Jew, more than six hundred years after he penned them:

My heart in the East

But the rest of me far in the West –

How can I savor this life, even taste what I eat?

How, in the chains of the Moor,

Zion bound to the Cross,

Can I do what I’ve vowed to and must?

Yet gladly I’d leave

All the best of grand Spain

For one glimpse of Jerusalem’s dust.

Other parts of the toolkit were developed in the Safed (a Galilean city) Renaissance of the 16th century and diffused throughout world Jewry. Perhaps most notable was an addition to the liturgy that quickly spread around the Jewish world, Alkabetz’s Lecha Dodi (“Come my beloved”) which came to be sung in synagogues worldwide every Friday night. At the heart of Lecha Dodi is a mixture of the theme of welcoming the “Sabbath bride” with prayers for the return to Zion (with Israel as God’s bride), and the rebuilding of Jerusalem:

Do not be ashamed nor confounded.

Why should you be downtrodden and why should you be shocked?

Within you the afflicted of My people will seek refuge.

And the city will be rebuilt on its former site….

And your oppressors will be destroyed.

And those who would devour you will be far away.

Your God will rejoice over you. Like a bridegroom rejoices over his bride.

To be clear, the fact that Jews throughout the world had access to a common cultural toolkit, one that included a wide variety of ways by which Zion was centered (and the claims of current denizens of the land rejected) hardly meant that the Zionists had it easy. There were all kinds of good reasons not to move to Palestine. Moreover, the Jewish cultural toolkit also included a wide array of ways of coping with life in the diaspora, as Jews had managed for 2500 years.

But no one pursued nation states before the 19th century. And every nationalist movement had its opponents, from both left and right, among the co-ethnics/co-religionists that were meant to form the would-be nation.

And if any co-ethnics/co-religionists had the elements of nationalism in their cultural toolkit, Jews certainly did. It just so happens that as a people who were largely exiled from their homeland, realizing their ancient dream would require them to adopt an array of tactics that echoed settler colonialist movements of the same period.

It is then not so surprising that those who have come to oppose the legacy of European empire, and of settler colonialism in particular, would come to oppose Zionism as strongly as they do. Unless you are a Jew or (you are a Christian and so) have some sympathy for the ancient Jewish longing for Zion, what would lead you to apply both nationalist and SC frames to Z/I? It’s so complicated! And especially if your life’s work is to attack empire and SC in particular, it follows that you are likely to do as Wolfe did: Damn Israel by caricaturing it as settler-colonialism on steroids.

But if our goal is explanation rather than moral judgment, a more productive analytic path is available, one that recognizes each framework is essential because each framework is deployed by each of the two sides— in contrasting ways— to understand themselves and the other.

Coda 2: Settler Colonialism Cuts Both Ways

My second and final concluding point fleshes out this last point. In particular, a premise of the discussion to this point is that the only lumping vs. spliting debate pertains to Zionism/Israel. But what about Palestinian nationalism? In particular, just as Palestinians and their supporters like Wolfe tend to frame Z/I in purely settler-colonialist terms and thereby deny Jews their claim to be a nation (at least one with a claim to the land), supporters of Israel have a tendency to flip the script, sometimes quite effectively. Consider the image below, which was taken from a Pro-Palestine demonstration in London in early February 2024. The protestor thought they were being clever by saying that the Jewish claim to any land is flimsy because Jews really belong in “Jahannam”— the Muslim version of hell.

Setting aside the ugliness of declaring that all Jews (or maybe just Zionists?) belong in hell, what this protestor apparently does not know is that the Muslim term for hell unwittingly attests to the deep Jewish connection to Zion. That’s because Jahannam is an Arabic loan-word from Hebrew, where it refers to a valley just below Mt. Zion, the valley of Hinom = Gei ben Hinom. The Wikipedia article on this is quite good, as it traces how this valley came to have dark associations going back to bibical times and how Jewish ideas about this valley found their way into Christianity starting in the 1st century CE and into Islam beginning in the 7th. The upshot is that the sign is a reminder that Jews are as native to the region as anyone, Jerusalem (Zion!) in particular; and that Islam and Arabic culture and language— which arrived in the region later, on the strength of the imperial sword— bears witness to this. Recall above that this idea is central to Halevi’s poem and to Alkavetz’s song. In the first instance, Jews regard both Christian and Muslim presence in the holy land as symptoms of illegitimate, imperial conquest.

A related phenomenon attested in pro-Palestine social media posts is showing how various Hebrew place names used by Israelis involve rewriting “Indigenous” Arabic place names. The problem though is that in many of these cases, the original names were actually Hebrew (or Canaanite but attested in the Hebrew Bible as maintained by Judean and/or Israel). So in these cases too, attacks on Jewish/Zionist dispossession based on ignorance of pre-Islamic history ends up providing unwitting attestation to the deep Jewish roots in the land, and indeed to Jewish dispossessions by imperial conquerors, including Arab Muslim conquerors.

And so when attacked as settler colonialists, it is straightforward for Zionists to flip the script. As noted in part a, the obvious rejoinder is to assert that ancient history is irrelevant. But this is hardly persuasive. If dispossession must be regarded as worthy of recompense 75 years after it occurred, why should two thousand-year-old dispossession be any different? Why indeed shouldn’t it have precedence? Nor is it particuarly effective to claim that today’s Jews have no connection to the Judeans of late antiquity. Try finding the break in history if you can. And in any case, Jews and Christians both believe the Jews of today are the same people as Second Temple era Judeans. Good luck trying to persuade them different.

Personally, I don’t think these claims and counter-claims can be effectively adjudicated (nor does it help to, e.g., bring in Jewish claims to dispossession from Arab countries during the twentieth century). How the heck do we decide what the statute of limitations is on historical wrongs? And who is responsible for correcting these wrongs? I have no idea.

It is productive, however, to understand the nature of these claims and counterclaims. They are deeply rooted not just in a wide body of facts selected and interpreted to fit each narrative but, as Penslar shows, in deeply and widely felt emotions. These emotion-fueled narratives in turn drive action.

If we want to understand the dynamics of the conflict, and why it is so intractable, we cannot simply pick the side we think is right. We have to understand why the parties act as they do. And that means that the question of whether Z/I— or Palestine— is a case of SC or nationalist liberation— is a distraction from the important question of why each side tells a story of national liberation about itself & a story of SC about the other, but they struggle to reckon with how they diverge in lumping and splitting. Indeed, not only does each side tend not to accept the other side’s narrative, each tends to be uninterested in what the other side believes about its own narrative and how this affects its behavior.

This is a point that has been made by several prominent Israeli commentators recently, most notably by Yossi Klein Halevi and Haviv Rettig Gur. Each of these writers is eloquent in articulating the Jewish/Zionist narrative and is perplexed and disappointed that they cannot seem to get Palestinians to be interested in understanding that narrative. In an interview on Russ Roberts’s Econtalk podcast in December, Rettig Gur argued persuasively that Palestinian lack of “curiosity” about the Zionist narrative dooms them to repeated failure, as they operate under the Palestine=Algeria by trying to chase Jews off the land even as Jews responded by renewing their commitment to their homeland. This is consistent with what I argued in part a, and fleshed out further here.

But Rettig Gur’s lament about Palestinian incuriosity deserves more attention: Why indeed aren’t Palestinians more curious about the Zionist narrative? This is an extremely important question, as is the flipside of that question: what causes Jews/Israelis to be curious about the Palestinian narrative, if indeed they are?

My sense as a social scientist is that this is relatively uncharted territory. I am unaware of any systematic theory of what we might call “the question of social curiosity”: What motivates us to be interested in why other groups are as they are, and do what they do? And does a conflict with another group increase or decrease such curiosity? I’ll try to sketch some ideas in my next post.