Age-Old Wisdom from an Ancient & Seemingly Disturbing Story

When it comes to wood gathering, a shift in perspective makes al the difference

In the early stages of writing The First Week1, I realized that I faced an unusual rhetorical challenge.

To wit:

As far as I’m aware, every other book that engages extensively with the text of the Hebrew Bible assumes a reader who cares about this text and is in one way or another conversant with it. Such readers include religious Jews and Christians. They also include scholars of Bible and religion who are professionally committed to setting their personal religious commitments aside (if they have them) when reading the HB. Then there are secular Israelis and other Jews who see the HB as important to their cultural heritage. And there are also those who are interested in the cultural foundations of the West, of which the Bible (HB as well as New Testament) is a key part. And finally, there are those who are interested in the HB as an example of ancient Near Eastern literature.

In my book, I will definitely want to reach such readers. But if I only reach them, and if I reach such readers for one of the aforementioned reasons, my book will be a failure.

Why?

Because my book is about the launch of a temporal platform— the seven-day week— which has become the day-to-day rhythm of humankind almost universally (there are still indigenous tribes who don’t live by the week) irrespective of whether the humans in question know or care about the HB.

Moreover, my argument is that the “first week”— i.e., the invention and launch of the 7-day cycle— was a stunning turning point in human history, and that this is the case from a (social) scientific perspective, it is essential that it not be regarded as a book about religion.

But then why include in the book an engagement with the HB? Why risk alienating so many readers for whom the Bible is unfamiliar or even anathema? Indeed, even many folks who are biblically conversant may be turned off by the use of the HB for scientific purposes.

There are a few related reasons for this, which I’ll discuss in the introduction to the book. Basically though, the book won’t work unless the ‘scientific’ case for including the HB is readily grasped by the reader.

Good news! I believe that this seemingly impossible task is quite feasible. Sure, there will be many readers I’ll fail to reach. But I’m quite confident that I can reach many of the readers I covet with this strategy. How do I know this is achievable?

Well I’ve been working on this book for a looooooooooooong time now (depending on how you count, it’s ~30, 13, or 9 years). And from lecturing and writing about pieces of it, I have a good amount of feedback now on how people react to it, including my engagement with the HB.

In particular, for the past 7 years, I have been publishing essays in the online journal Lehrhaus.2 This outlet has been invaluable to me for experimenting with a rhetorical style that might reach these coveted readers. Virtually all of these essays are treatments of puzzles in biblical texts using some combination of sociological theory (my stock and trade) and literary analysis (of the type that has flourished among academic and Jewish scholars of the HB in the last two generations, informed by discoveries on the literary conventions of ancient near eastern texts). And what I’ve found is that these essays have often resonated with those coveted readers. That has been very encouraging and gratifying indeed.

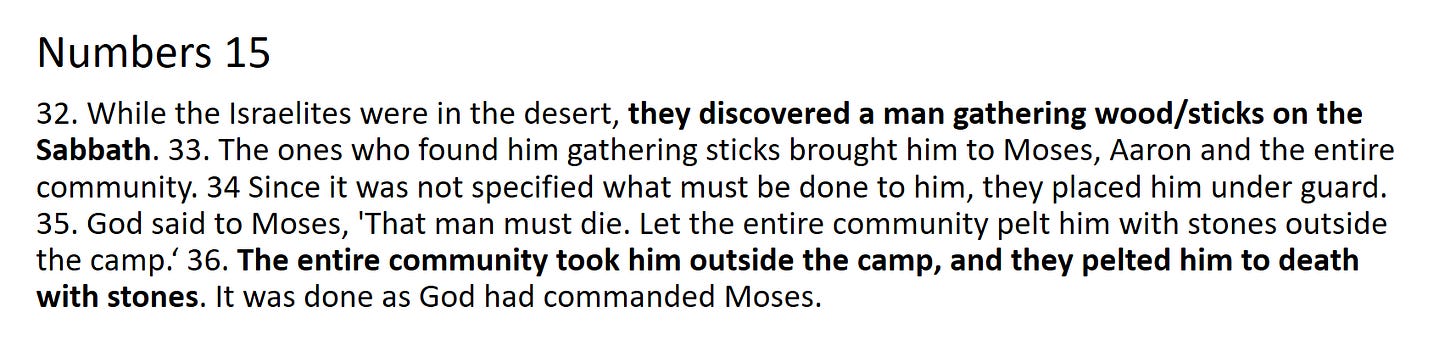

As an example, consider a very short story— from a section of the book of Numbers that’s read in synagogues worldwide tomorrow:

This text seems absolutely insane to any modern reader. Stone a man to death just for gathering wood??!! No wonder that ‘Old Testament God’ got such a bad reputation!

More generally, it seems hard to understand how (as is stated explicitly in Exodus 31 and 35), violation of the sabbath is a capital crime! Indeed, this seems crazy from a Jewish perspective too. On the books, Sabbath violation is indeed a capital offense. But in practice, the requirements placed by the rabbis for enforcing it are impossibly high and there is no record of anyone ever being put to death for it. Heck, a famous rabbinic dictum suggests that even murder was rarely treated as a capital offense, and it never even occurs to anyone that a rabbinic court put anyone to death for sabbath desecration. What’s more, the Jewish people— as evocatively described by R Abraham Joshua Heschel— have a long-term love affair with the sabbath. So why would a regime of fear ever have needed to be implemented? Why would the HB make it a capital crime and include a story about this actually occurring?!

It turns out that the story of the wood gatherer is hinting at the answer if you read it from the right vantage point.

What do I mean?

Well, you can find out if you read any of three essays linked below, as well as (when I publish it!) my book.

(Yep, this post is a teaser! You didn’t think I’d just toss off a key part of the book in a substack post, didja? :-)

But here’s a very loud hint, drawn from my colleague Lily Tsai’s insightful book When People Want Punishment:

Cool, right!? I was so happy when I found this modern version of the wood gatherer story, one that was right in line with my interpretation of it!!

And now here’s a question that moves us even further along in answering our question:

Q: When you think about the biblical wood gatherer in light of the Chinese wood gatherer, what problem would you say they were trying to solve?

Answer is below the jump (with elaboration in the essays)

Links to essays:

"Between Shabbat and Lynch Mobs" Here I use both modern social science and literary analysis of 3 biblical narratives that are ‘intertextually’ linked with the wood gatherer story to show how the HB is driving home a point about why the sabbath would have needed to be enforced so strictly at that stage in history and the more general lessons about the human condition this entails.

How to Curtail Pernicious Social Competition: The Legacy of Zelophehad and his Daughters.3 Here I develop a hint in an ancient rabbinic form of literary analysis (midrash) that’s in line with my theory above, showing that the wood-gatherer story is a prelude to a wider and deeper analysis of the dangers of pernicious social competition (oops. that’s a strong hint as to the answer to the question!), one with startlingly pro-feminist aspects.

The Triple Threat to Social Order. Here I show that the wood-gatherer story can be usefully seen as the second part of a three-act set of vignettes about the factors that undermine social order, one that's better than the modern version (the prisoner's dilemma). The primary reason for this is that the biblical vignettes allow us to see 3 distinct factors that can undermine social cooperation and thus social order: greed, fear of greed, & rage.

Answer:

By now, you surely have your answer: the wood-gatherer story is an ancient take on Garrett’s Tragedy of the Commons.

Shabbat Shalom/Happy Weekend!

P.S. While social scientists since Hardin, most notably the Nobelist and Political Scientist Elinor Ostrom, have identified conditions under which the tragedy of the commons can be more easily solved, these solutions are either implicitly or explicitly ruled out in the case of the launch of the seven-day week. Why do I say this? Read The First Week when it’s out!!

Hoping and praying I finish it in 2024. Quiet in the world and on campus would really really help, if only by removing excuses for procrastinating…

I am deeply grateful to the founding editors Zev Eleff and Elli Fischer who first invited me to submit, and to the editorial team for their help in shaping the essays.

Not my stock and trade! But I got very excited about it around 2000 and have worked hard for the last 25 years to absorb and develop my skills, building on the strong foundation in Hebrew and Jewish texts I was lucky to receive in my childhood (and my ongoing experience as a baal koreh)